One of the largest debates in the world of photography is split into two main camps. On one side are people who strive to take photos with the highest technical level of image quality — in everything from their equipment to their camera settings — for most of their photos. The other side of the debate says that photographs are more about the subject and emotion of the scene, and the image quality is only a minor factor. Neither side is always right or always wrong, of course, but this is a question worth discussing. When does image quality truly matter, and when is “good enough” more than enough?

1) Genres of Photography

More than anything else, I am a nature photographer. I do take occasional pictures of people, but the backbone of my portfolio is of the great outdoors — from macro scenes to grand landscapes. That also means that my perspective on this question is a bit one-sided.

Not all genres of photography have the same image quality concerns. For example, many street photographers intentionally shoot with grainy film (or add film-style filters in post-production) to make their images appear grittier and timeless. I haven’t worked with this genre enough to have a well-considered point of view.

So, this article focuses primarily on nature photography. Similar compromises exist in every field, from weddings to still-life, but this article is mainly geared towards people who shoot landscapes.

2) Comparing Famous Photographers

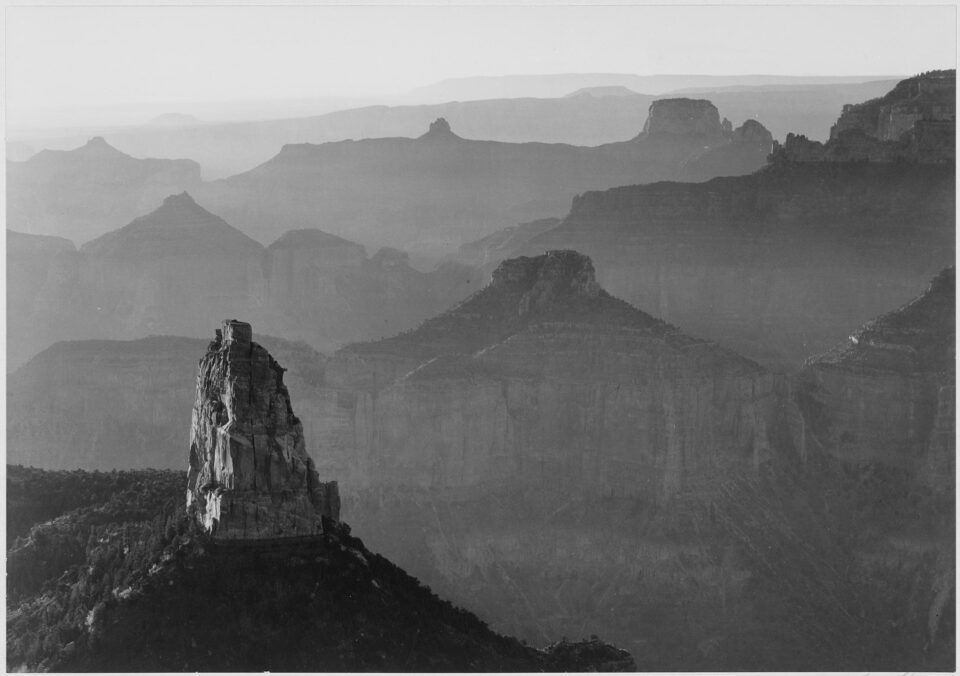

This is one of the major questions of landscape photography, and it makes sense that famous photographers fall on different sides of the “good enough” image quality line. On one end of the debate was Ansel Adams, history’s most famous landscape photographer, who (among other photographers) catapulted the idea of technical perfection into mainstream practice.

Other landscape photographers fall into a different camp. Galen Rowell is one of the more recent famous landscape photographers, and his work is also iconic. Yet, Rowell was known to take pictures with nothing but a simple 35mm camera with a cheap wide-angle lens and lightweight telephoto zoom. Why? Because he had mountains to climb.

The crux of this debate deals with the reasons people are willing to forego the “best” equipment in favor of other options. Although all photographers are different, this typically boils down into a few main factors: weight, price, and speed.

Galen Rowell needed the light weight and quick use of 35mm cameras. Many of his famous mountaintop and climbing photographs wouldn’t have been possible with heavy equipment. Sure, the technical quality of his photos suffered a bit, but his subjects were more important than the size of his film grain.

Ansel Adams, on the other hand, didn’t go on the same technical climbs that Galen Rowell was known for scaling. Instead, he had assistants — and occasionally a mule — to carry his gear long distances. Adams wasn’t sedentary by any means, and he backpacked quite a bit, but most of his landscapes were still reachable with his large and heavy equipment.

So, who took better photos? I’m not going there! These two incredible photographers simply had their own styles, and different types of gear suited them differently. Ansel Adams never would have gotten such large and dramatic prints with a handheld camera — especially in the mid-1900s — and Galen Rowell couldn’t have climbed to some of his most famous photos while carrying forty pounds of camera gear.

3) Camera Settings

Between Ansel Adams and Galen Rowell, the main image quality difference was due to the camera equipment that they used. This matters in your own photos, of course, which is why camera manufacturers offer so many different choices. However, another variable is at play: the amount of time that you take to set the proper camera settings.

At first, this seems like a no-brainer. Obviously, if you have enough time to take your photo, it makes sense to use the best possible camera settings. Right?

Maybe not. Do you use UniWB and check the histogram for every shot, making sure that you always expose to the right? Do you always measure the distance to your closest subject and focus at double that distance, the hyperfocal point? Do you choose the aperture that provides the mathematically best compromise between diffraction, lens sharpness, and depth of field?

For most photographers, the answer is no. I wrote those articles, and I still rarely take my photos with proper hyperfocal distance, the ideal aperture, and perfect ETTR, all at the same time. I may — and typically do — one or two of these things, but the whole set would take ages for every photo.

Plus, things don’t stop there! I could focus stack every single image at f/5.6, since that’s the sharpest aperture on my lens. I could take a set of five bracketed exposures just to make sure that my exposure is as perfect as can be. While we’re at it, why not make every image a panorama? That way, I could get triple the pixels (or much, much more with a multi-row panorama).

And there’s the other problem. Even though memory cards can fit thousands of photos, no one wants to spend thirty minutes on a single landscape image — especially when it might not turn out well. Once you start searching for the absolute best image quality, you rapidly begin to change the fundamental way that you take pictures, and not in a positive way.

So, “quick” camera settings make it easier to photograph a scene — and, most likely, take many other photos in the same amount of time. Sometimes, as crazy as it sounds, I even put away my tripod when the light is at its best. I then set down my camera bag and run to the best possible location, taking photos from the best vantage point before the light fades away.

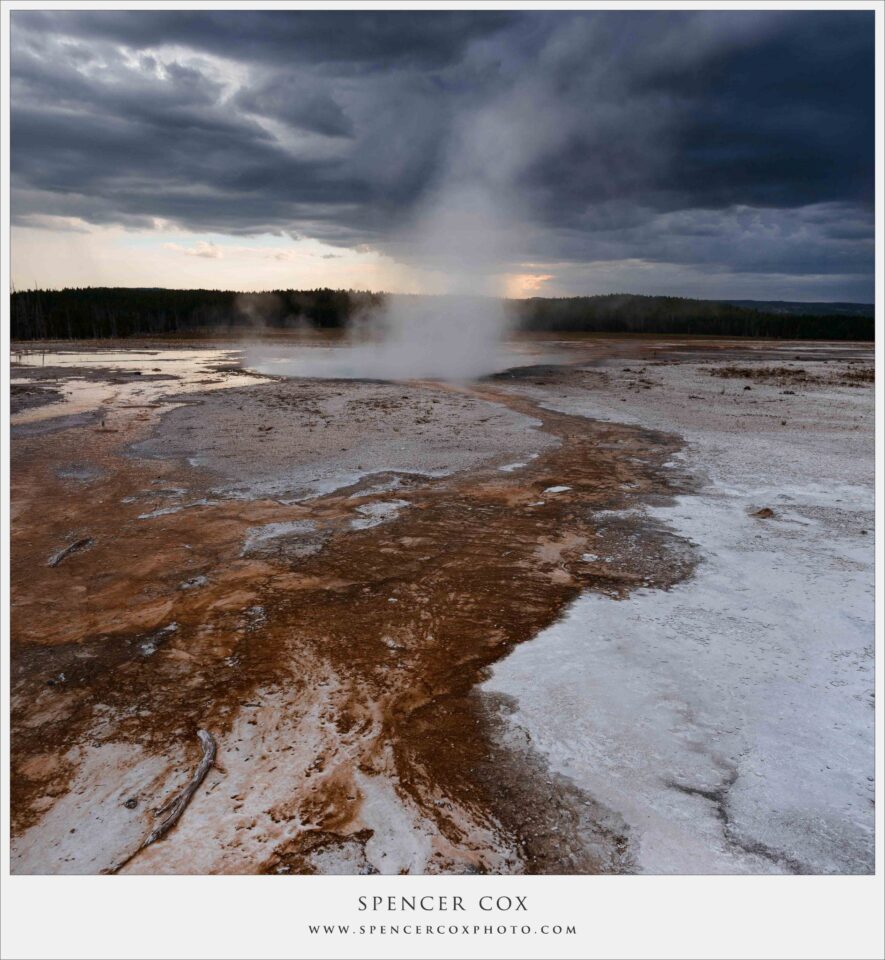

NIKON D800E + 20mm f/1.8 @ 20mm, ISO 110, 1/50, f/7.1

I took this photo without my tripod and used a relatively wide aperture of f/7.1. Here, the bottom corners are ever-so-slightly less sharp than the rest of the photo. Is that a problem? Not for me. I’m happy to have this image in the first place, and the difference wouldn’t be noticeable at any reasonable print size.

Yes, I would prefer to have a photo taken from a tripod. But, in the long run, is there anything wrong with one stop higher ISO, or a slightly wider aperture? I take 95% of my landscape photos with a sturdy tripod, if not more, but there’s always occasion to put it down and run to the best vantage point as fast as possible.

Of course, this isn’t an excuse for photographing everything at the wrong shutter speed, without a tripod, and at bizarre ISO values. Instead, it presents another question. Do you want to take a landscape photo that, in all likelihood, uses settings that will work just fine? Or, do you plan to eke out every possible pixel of image quality for large prints and high-resolution displays?

4) The Effects of Modern Technology

Modern cameras have driven image quality forward throughout the past decade in two main ways: number of pixels and low-light image quality. These two variables may be crucial for your work, or completely unimportant, but there is no doubt that these are the main still-photography features that camera manufactures are interested in iterating. (Matters like dynamic range and color depth are certainly important to camera manufactures, but they aren’t advertised in the same way as pixels and high ISOs.) How does this change the way we look at image quality today? If anything, it makes the two camps even more divided.

For one, it is now much easier for photographers to print high-quality images several feet or meters wide, even without paying thousands of dollars for camera equipment. Until the past five or ten years, that was very difficult. Although 35mm film has a surprising amount of detail, it doesn’t have the same resolution as modern digital sensors. (Film obviously has other advantages for some photographers, of course.)

At the same time, it is easier to carry lightweight camera equipment and shoot at higher ISOs than ever before, still taking relatively high-quality images. If you want to hike up the side of a mountain, mirrorless cameras — and even some point-and-shoots — have incredible quality today.

So, where does this leave us? It’s easier to take ridiculously-high-quality photos today, but it’s also easier to take “good enough” photos with equipment that is still very lightweight. This is surely a good thing, but it does make our decisions more difficult.

5) Compromise

In the end, everything is a compromise. Image quality is a sliding scale; the more quality you get — typically — the slower you will need to work. Achieving the perfect balance can take years of trial and error, but most photographers find their fit at some point along the way.

My own photography can serve as an example. Surprisingly — or not — I shoot most landscapes on my Nikon D800e at f/11 or f/16. I absolutely understand the effects of diffraction from these settings, but there is a huge benefit: I don’t need to take extra time to check my depth of field for every photo. I already know that I have enough, no matter the landscape.

Why am I willing to make this particular compromise? It’s simple. After printing dozens of my photographs at large sizes, from 24 inches to 60 inches wide, I realized that the difference is too small for me to care. Not everyone will make the same judgement call, but that’s what this ultimately is: a judgement call. An aperture of f/16 adds some pixel-level blur, but it also makes it easier to take more compositions in the same amount of time. Ultimately, I realized, this nets me a greater number of successful photos.

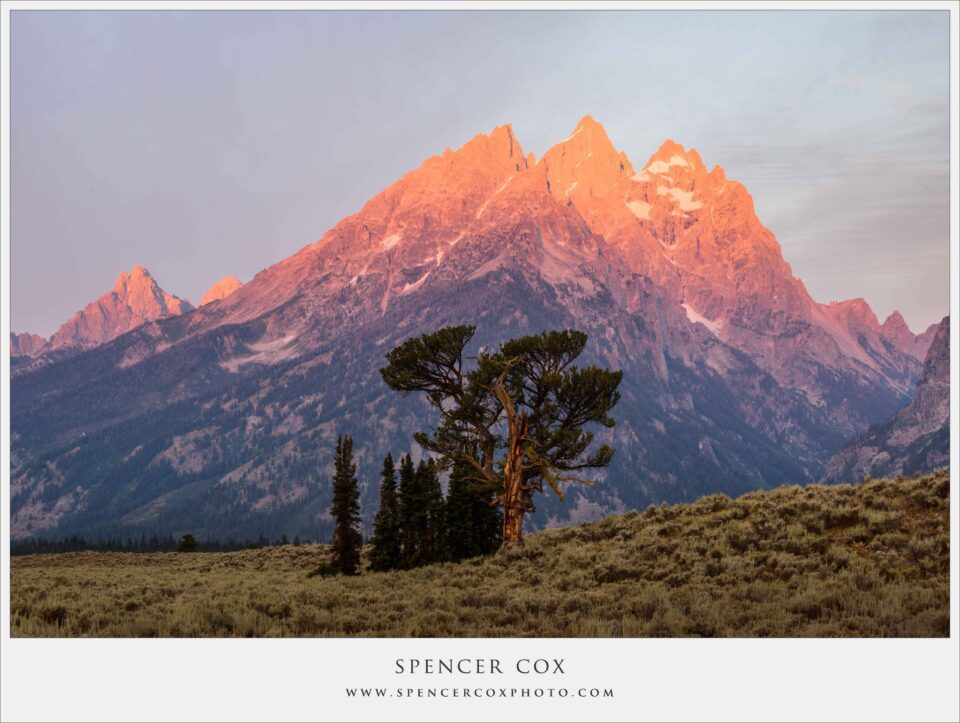

NIKON D800E + 70-200mm f/4 @ 70mm, ISO 100, 3/5, f/16.0

This was shot at f/16. Would f/8 have provided enough depth of field? Maybe, and maybe not. (This was a telephoto shot, which complicates the question.) Because I shot at f/16, though, I didn’t have to worry about depth of field — only composition.

As with everything in photography, the real goal is to go out and answer this “good enough” question yourself. Do you routinely print enormous photos on acrylic? Ideally, you would shoot with a high-resolution camera — even medium format — or perhaps a 4×5 or 8×10 film camera. Do you sell digital downloads of your work at 1920 x 1080 resolution? By all means, get a lightweight camera that makes it easier to reach interesting places.

That’s why today is such a good time to be taking pictures. As much as we like to find fault with new cameras and lenses, the fact is that we have more options than ever before. In everything from cameras to tripods, manufacturers offer an incredible range of options: price, size, image quality, and every other possible variable.

Although too many choices can make our decisions more difficult, it also means that we are able to take the photos we want with much less compromise than in the past. As a community, that is something we should embrace to its fullest.

The post The Question of “Good Enough” Image Quality appeared first on Photography Life.