For the past couple years, I have thought of myself primarily as a “telephoto” landscape photographer. A majority of scenes that catch my attention look best with a telephoto lens, and I tend to keep a 105mm or 70-200mm on my camera most of the time. However, a recent trip to Zion and Death Valley National Parks changed my mind.

To put the change into context, consider the percentages below. These show the lenses that I used when I went to Iceland, where I took about 2300 photos:

- 35% from my 24mm

- 12% from my 50mm

- 53% from my 105mm

In Zion and Death Valley, where I took about 1350 photos, my choices were skewed the other way:

- 67% from my 20mm

- 4% from my 35mm

- 29% from my 70-200mm

(If you are wondering how I came up with the above data, see Nasim’s “what lenses do you use the most?” article).

On one hand, it seems that I don’t use “normal” focal lengths – 35mm and 50mm – very much at all. More interestingly, though, was the switch from telephotos to wide-angles. As much as I favored a 105mm in Iceland, I preferred the 20mm even more in the American Southwest. So, what’s going on?

1) Differences in the Landscapes

Iceland and the American Southwest are vastly different places. Aside from the incredible amount of wind in both places – at least when I went – the landscapes themselves could hardly be less alike. One is icy and dark, while the other is bright and orange. The sweeping lines of the American Southwest have no parallel in Iceland’s gravel-filled, ever-changing landscape. Both, of course, are amazingly beautiful.

Wide-angle lenses, by exaggerating the relative size of nearby objects, are conducive to photographs with a dramatic foreground. The sweeping rock formations of Zion were perfect for this purpose, offering leading lines that swept through the frame. Nearly every inch of Zion’s winding rocks could be used as a foreground, which offers a strong case for wide angle lenses.

Does that mean that Iceland doesn’t have interesting foregrounds available? Not at all. Although I would argue that there are not as many, foreground elements certainly exist in Iceland’s landscape as well. From melting icebergs to streams of water, several Icelandic landscapes provide a way to anchor your composition. However, in many places, Iceland is covered with patches of moss intertwined with black gravel. Unless you want an ambiguous rock – or a man-made road – to sit at the base of a photo, it can be difficult to find an adequate foreground.

At the same time, many of Iceland’s landscapes were far in the distance. As much as I wanted to hike to every distant waterfall, it wasn’t always possible. However, Iceland’s relatively empty landscape meant that it was easy to photograph distant objects without being blocked by anything in the foreground; I simply needed to switch to a telephoto lens.

Zion, by contrast, was filled with narrow canyons and winding rivers. These almost necessitated a wide angle; the landscape is so close that a telephoto lens wouldn’t do any good. Without a wide angle lens, there was no easy way to show the sweeping lines of rock. Very few landscapes were distant enough that they warranted a telephoto.

2) Changes Over Time

I photographed Zion more than eight months after I went to Iceland. Eight months is nothing trivial; in that time, I overhauled my set of lenses and spent far more time practicing composition. So, could it simply be the stretch of time that led me to favor some lenses over others?

Although it certainly is possible, I would be surprised if the differences are entirely due to a change in my personal approach to landscape photography. I have favored a similar style of lighting and contrast, as well as post-production, for quite a while; these didn’t change significantly following my trip to Zion. Most of my stylistic choices have remained fairly constant.

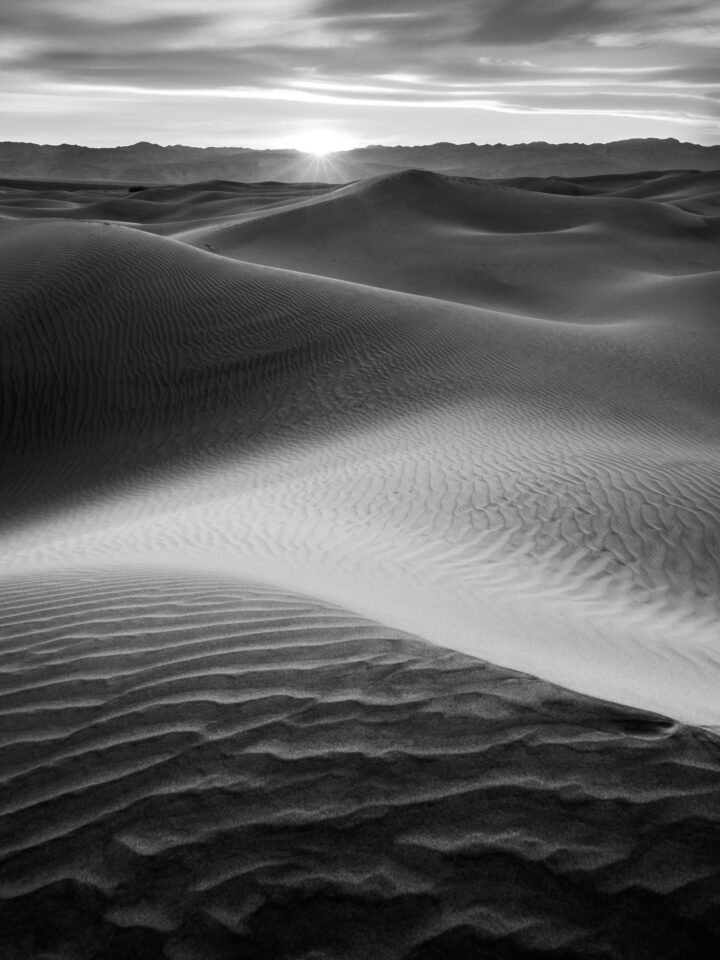

However, one change that I did notice in the American Southwest was my growing tendency to take vertical photographs. Only a tiny handful of my photos from Iceland were taken vertically – and even those were mostly to be stitched into horizontal panoramas. In Zion and Death Valley, by contrast, almost a third of my images were vertical (including three of the four in this article). That is a pretty significant change.

In part, of course, that change is due to the landscape itself. Vertical images can show a larger foreground, which makes them perfect for places like Zion and Death Valley. However, this doesn’t account for all of the differences. Some areas of Iceland, such as Jökulsárlón beach, are well-known for their incredible foregrounds. However, although I spent three days at Jökulsárlón – primarily using my wide lens – I didn’t take a single vertical photograph while I was there.

So, perhaps the result would be different if I visited Iceland again today. I certainly have changed in many ways as a photographer, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see old subjects from a different perspective. However, even given my changed mindset on vertical photographs, I still believe that the most significant difference between Zion and Iceland was in the landscape itself.

3) In Context

For several years, the widest lens I had used was a 17-55mm lens on my D7000 (which is around a 26mm full-frame equivalent). Before that, I used my 105mm lens, also on the D7000, for nearly a year, never swapping to anything wider. I only moved to full frame a year ago, and I haven’t had the 20mm f/1.8 for more than six months.

All this is to say that my personal experience is not particularly normal. In some sense, there is no “normal” path that photographers tend to take. You may have a single 28-300mm lens, or you could have a set of primes stretching from 15mm to 500mm. And, no matter your kit, it is almost impossible to avoid feeling preferences for certain focal lengths over others. The key is to recognize the biases that you have and try to ensure that they aren’t getting in the way of taking good photos.

At the beginning of this article, for example, I mentioned that I rarely use “normal” focal lengths, such as 35mm or 50mm. Although this certainly was true in Iceland and Zion, who says it will be the case anywhere else? If I get into the wrong mindset from this information, I very likely will overlook incredible photos.

This effect seems particularly true with zoom lenses. Say, for instance, that you have a 24-70mm zoom. At one location, you may take every photo at 24mm. Somewhere else, you may shoot several photos zoomed in to 70mm. The danger, then, is that you begin seeing yourself as a photographer who doesn’t like or isn’t good at taking pictures with the in-between focal lengths. That puts you in a self-fulfilling cycle, and the variety of your photos will suffer as a result.

So, no matter your specific situation, be aware of the mindset that you bring to the field. If you see yourself as a wide-angle photographer, remember to carry along a telephoto lens. Or, if you always use a 70-200, be sure that you are aware of ultra-wide possibilities. It is easy to get caught up with the focal length that you are using at a given moment – or the focal length that you tend to use – but that doesn’t make it the best possible way to photograph a scene.

4) Conclusions

Each time that you take a picture, you should thoughtfully consider the variables at play. Everything from your camera settings to your composition is important to consider, and it is likely that you do think about these things as you take pictures. But, if you find yourself using the same focal length even at completely different landscapes, you may be overlooking other possibilities.

There is nothing wrong with having a favorite focal length. I’m still partial to my 105mm, and many of history’s famous photographers shot solely with a 35mm or a 50mm lens. The important point, though, is to make sure that you think consciously about your choice of lens before taking a picture. If you use your favorite focal length without an active reason, you may be missing out on better photographs. That certainly was true for me; a lingering “telephoto mindset” cost me some early wide-angle photographs in Death Valley.

My takeaway, then, is the importance of picking a focal length on a case-by-case basis. It can be tempting to stick to one particular focal length – particularly one that you find comfortable – but that approach can limit your frame of mind. A given lens may shine in the Smoky Mountains, yet be completely unusable in the Pacific Northwest.

Photographers always want to take the best possible pictures at a location, and our biases sometimes get in the way of that goal. By making conscious decisions about every aspect of an image, you can ensure that your photographs are as good as possible.

The post Different Lenses for Different Landscapes appeared first on Photography Life.