The sweltering January sun offered little respite from the hounding mosquitoes which prowled the ruins of Chichen Itza in the Mexican Yucatan. Known since the early years of the Spanish conquest, the once glorious city had been eroded by centuries of isolation by the time British explorer and archaeologist Alfred Maudslay first set foot there in 1888. While strong willed and greatly experienced by his previous forays in the ancient Mayan cities of Guatemala, Maudslay endured tremendous hardships for his ultimately successful creation of a detailed plan of the extensive ruins of Chichen Itza. He set up camp in one of the chambers found on top of the building known as Las Monjas (“The Nunnery”) which had served as a palace for Mayan royalty over 800 years before. It is from this base camp that Maudslay was able to map out the site with remarkable accuracy and thoroughness, while also capturing a particularly iconic still photo of an overrun Pyramid of El Castillo among many others. In the final days of his expedition, after five months of hard work in the spiteful heat of the Yucatan coupled with a bout of Malaria, Maudslay’s health greatly declined to the point where he had to return home. It took him six months to recover from his ordeal, but his expedition to Chichen Itza would not be the last time he would venture deep into the heart of the Mexican rain forest in the hopes of documenting the lost relics of the Maya. In this article, I will go over some of the best photography locations in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico.

1) Chichen Itza

Today, the Pyramid of El Castillo is no longer blanketed by the jungle that had once devoured the entirety of the site. Partially cleared of the heavy undergrowth, the ruins at Chichen Itza and the other ancient Mayan cities which dot the Yucatan are far more accessible then they were in Maudslay’s time. No longer is it necessary to traverse harsh terrain to reach the ancient cities, nor is it imperative to sleep inside the ruins themselves. With modern hotels a short walk away from most of the archaeological sites and with clearly defined pathways inside them, traveling to see the lost cities of the Yucatan has never been easier.

Beginning south from Cancun into the heart of the Peninsula and ending in the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico, our journey navigates between the most fabled of the Mayan cities while also exploring the relics of the Yucatan’s colonial past. Exactly 200km west of Cancun following highway México 180D, the Ancient City of Chichén Itzá has proven to be the most popular tourist attraction in the Yucatan Peninsula. An immense complex of both restored and unrestored structures, the city played an important role in the Yucatan’s history from about 600 A.D. until about 1000 A.D. The details of its past were mostly lost with the Spanish conquest of the peninsula in the 1500’s, but the ruins themselves are exceptionally well preserved with the crown jewel of the city being the world famous El Castillo Pyramid.

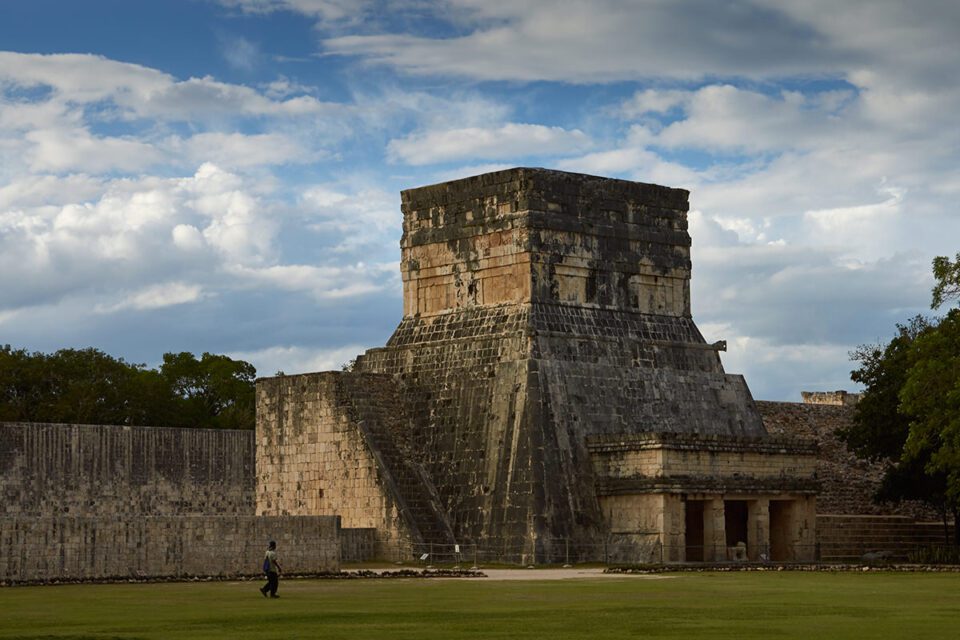

Towering prominently above the flat plain below, El Castillo is the first structure to greet newcomers to Chichén Itzá. Built over an older pre-Toltec temple, the 30 meter high temple-pyramid was dedicated to the Mayan serpent deity Kulkulkan (“Plumed Serpent”). The structure is actually a massive Maya calendar formed in stone. Each of El Castillo’s nine levels is divided in two by a staircase, forming 18 separate terraces that commemorate the eighteen 20-day months of the Mayan Year. The four stairways have 91 steps each which together with the top platform add up to the number 365, representing the number of days in a year. Tourists are no longer allowed to climb to the top, but with a bit of experimentation the pyramid offers excellent photographic opportunities. In the photo below I used a group of local school girls who were running a race around the base of the pyramid as a story-telling element to help convey the immense size of the structure.

North-West of El Castillo lies the Great Ball Court. An immense court used for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame, a sport not dissimilar to racquetball found throughout the Ancient Mayan world. The court’s call to fame is its immense size. Stretching over 168 meters in length and 70 meters wide, it is by far the largest of the 13 ball courts found in the city.

From El Castillo you can walk east toward the Temple of the Warriors and the Group of a Thousand Columns or you can head south in the direction of The Observatory. I recommend going to both though the former is quite difficult to properly photograph because of its immense size. The walk to the latter leads past the Osario and Casa del Venado group.

The small Casa del Venado is a small half standing building representing the western most section of the ruins at Chichen Itza.

El Caracol (“The Snail”) is located a few hundred meters south-west of Casa del Venado. It gets its name from the spiral staircase found within the observatory situated on top of the platform. The circular nature of the building has led researchers to theorize that it was used as an astronomical observatory, specifically to track the movement of Venus across the sky.

Lying at the southern tip of the city, the Edificio de las Monjas marks the end of the tour of Chichen Itza. Composed of number of different rooms and sections, the Las Monjas palace is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is in one of these rooms that Alfred Maudslay set up a study and sleeping quarters during his expedition to the city over 129 years ago. Next to the palace is the unique La Iglesia (“The church”) which is decorated with elaborate masks and hieroglyphic texts which tell stories of the city’s past. Below is an image taken of Alfred in his study inside the Las Monjas palace during his stay in the city.

While not known for its wildlife, the site is also home to a number of beautiful bird species which take refuge in the surrounding forests. With some patient forays into the side trails between the ruins, you can probably find some beautiful species like the colorful Motmot or Ocellated Turkey.

2) Merida

Moving west on highway 180D leads to to Merida. A crossroads between Chichen Itza and the Mayan city of Uxmal, Merida has long been the cultural capital of the Yucatan Peninsula. Steeped in colonial history, the city offers beautiful Spanish colonial architecture with especially beautiful churches of the era. The city is very much a tourist town, but its small size and more distant location separate it from the resorts that dot the Eastern shores of the Yucatan. At the heart of the city lies the Plaza Grande, the downtown’s bustling main square. From good ice-cream to interesting photo-ops of locals, the Plaza Grande is the best starting point for an exploration of the city.

3) Uxmal

Nestled near the Puuc (“hills”) region of the Yucatan an hours drive south from Merida on Mexico 261, Uxmal is among the most beautiful of the ancient Mayan cities. The name Uxmal means ‘thrice-built’ in Mayan. The name references the construction of its highest structure, the Pyramid of the Magician which was built on top of existing pyramids.

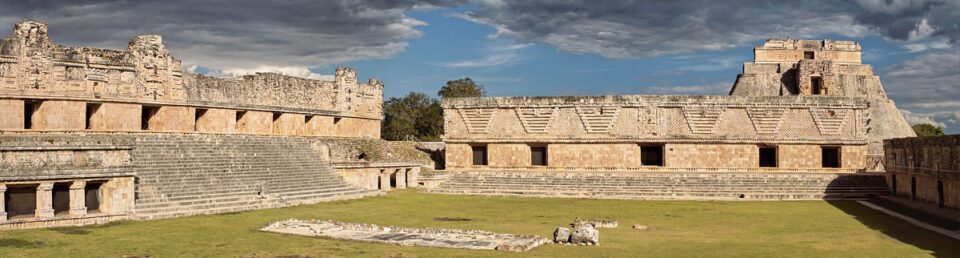

Akin to Chichen Itza, Uxmal flourished during the late Classic Period (around 600-900 AD) of the Pre-Columbian era before succumbing to the rule of neighboring settlements. Because of the city’s location on the Puuc Route, Uxmal is a distinctive example of entirely Puuc architectural style in contrast to other Mayan cities of the era which incorporated a combination of architectural influences. Buildings in the Puuc style are characterized by their simple lower sections, rounded corners, and small arched entry ways. The upper sections are highly decorated and reflect a distinct layering of stone work.

Greeting visitors immediately as they enter the archaeological site is the Pyramid of the Magician. The pyramid stands at an impressive 38 meter and was built on an elliptical base, an unusual style found in few Mayan pyramids.

Past the Magician’s Pyramid lies the Nunnery Quadrangle, a collection of four buildings composed of 74 small rooms that face an inner courtyard and thus create an enclosed space akin to a large nunnery. Each of the four buildings has a unique ornate facade making the Nunnery a wonderful example of typical Puuc architectural styles including Chac masks, serpents, and lattice works.

Situated atop a hill overlooking the Quadrangle is the Governor’s Palace. Constructed in the last days of the cities heyday, sometime around 987 A.D. the palace represents one of the best examples of Puuc architecture found in ancient Mayan archaeology. To the east of the palace lies the Great Pyramid of Uxmal which can be climbed and offers a beautiful vista of the ruins.

4) Calakmul

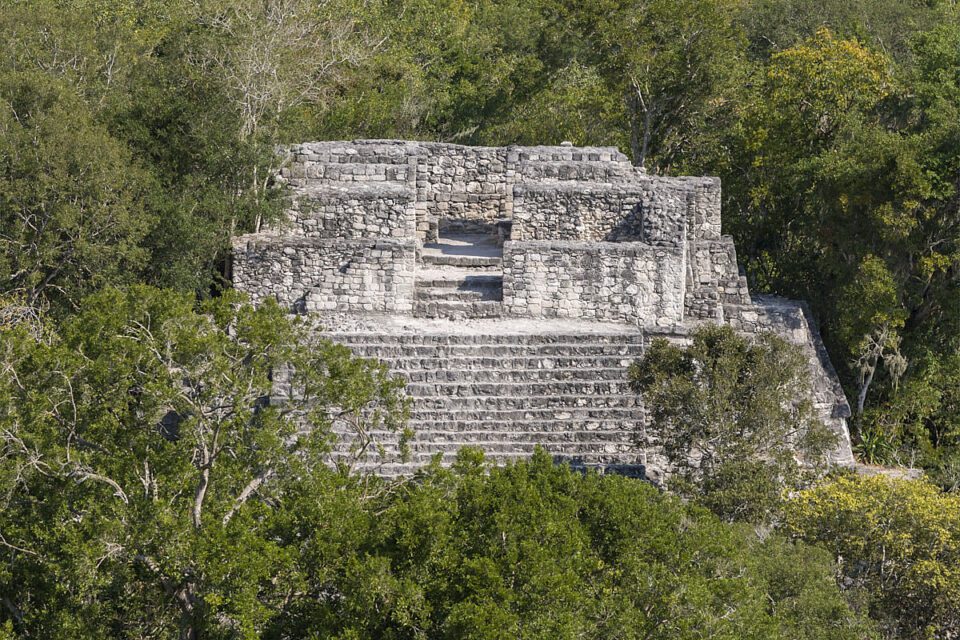

After winding its way along the coastline, Mexico 180D reaches a crossroads at Escarcega from where a left turn onto Mexico 186 leads to the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, making the overall journey a little over 400km. The 7231km reserve represents the last great tract of rain-forests found in Mexico, with most of the countries forests felled and cleared by human activity. The jungles host an immense biodiversity of wildlife, with 86 different species of mammals and over 385 species of birds. Concealed within the rain forest and just a few kilometers from the Guatemalan border hide the ruins which give the reserve its namesake, The Ancient City of Calakmul.

Meaning “City if the Two Adjacent Pyramids” in Mayan, Calakmul’s origins can be dated all the way back to 550 B.C. and was inhabited until its downfall at around 900 A.D. The city belonged to a coalition that included the Maya settlements of El Mirador, Uaxactún and Becan in the Mayan lowlands. Calakmul was the largest and most powerful settlement in this alliance, and was in constant conflict with its southern neighbors, mainly the city of Tikal located across the contemporary border of Guatemala.

Calakmul offers a wide variety of photographic opportunities for those who are patient. The archaeological site has far fewer rules restricting visitors as to where they can go and what they can climb, and as such, so there are many more opportunities for different compositions. The city’s restored central plaza consists of a large group of platforms and buildings to the west and a smaller group lying to the east. In between these buildings is the central zone with the Structure II pyramid. This pyramid is the largest in the Mayan world, with a base measuring over 120 square meters and tower at over 45 meters high. In fact, the pyramid is so large, that there is no way to take a photo of it in its entirety from the ground. After a tiring climb to the top, one which I do not recommend for those with a fear of heights, the rest of the city and surrounding forest can be seen for kilometers around. The Pyramid also offers wonderful bird watching opportunities because its height places you at eye level with the forest canopy, where the local toucans and parrots can be found.

The forests which have tamed the once great city offer a diverse range of wildlife for photographers with some patience and a keen eye. The rain forest’s floral composition is mainly a mixture of mahogany, ceiba and ficus trees whose seemingly endless canopies stretch as far as they eye can see. The reserve’s wildlife can often be found within the cities ruins, with views of Ocellated Turkeys, parrots and toucans quite common. It is also possible to see or hear spider and howler monkeys, with large groups of the endangered Geoffrey’s Spider Monkey often seen foraging from one fruiting tree to the other.

The Endangered Geoffrey’s Spider Monkey foraging for fruit:

An Endangered Geoffrey’s Spider Monkey foraging mother and son:

Other more shy bird species are also present at the site and the surrounding reserve, but it takes some patience and understanding of their behavior to locate them.

The shy Mottled Owl resting out the hot midday sun in the under canopy:

A Pale Billed Woodpecker with its nest in a tree cavity:

Always heard but almost never seen, the elusive Curassow go out of their way to remain hidden from any would be photographers:

5) Palenque

From here, our journey shifts outside out the Yucatan on a four and a half hour drive on Mexico 186 to the state of Chiapas. It is here, situated in the Tumbalá mountains, that the Mayan city of Palenque was built into the side of a hill overlooking the lush jungles below. Though quite small in size, the city’s combination of geography along with its delicate platforms, temples and palaces gives it a unique sense of artful harmony.

Greeting visitors upon entering the city, The Temple of Inscriptions, constructed sometime in 675 A.D. in honor of King Pakal, is perhaps the most important structure found in the city. Pakal the Great reigned in Palenque from 615 to 683 A.D. and is thought to be the most significant ruler in the city’s history. Upon his death, his first son was appointed ruler and ordered the construction of the Temple of Inscriptions as both a tomb for his father and as an homage to the city’s history.

Equally impressive is The Palace, a complex of several connected and adjacent buildings and courtyards which served as a home for Mayan aristocracy. Carved within the buildings hallways are numerous sculptures and bas-relief carvings which hint at the structure’s glorious past. Perhaps the Palace’s most unusual and recognizable feature is the four-story tower known as The Observation Tower.

The Temple of the Count, named after a French explorer who resided there during his visit to the site in the 19th century.

The archaeological site’s lush rain-forests are home to a range of different wildlife. A species which is often heard but not seen is the Guatemalan Black Howler Monkey. Found high up in the tree canopy, they can prove difficult subjects to photograph, but with some luck you can capture reasonable photographs and hear their mighty call. They are most active late in the day and it is well worth spending the late evenings looking for the monkeys up in the high canopies while the soft reddish glow on the branches signals the end of the day and our journey.

From Palenque, it is a grueling 8.5 hour drive back to Cancun. Yet reflection on the drive back rarely comes to mind while gazing down Palenque’s vast stretches of thick canopy from atop The Palace. It is tempting to think that here is nature’s domain and the search for wonders of a lost peoples a mere pipe dream, that the overpowering ferocity of the forest’s regenerative power is insurmountable. Perhaps in 1890 when Maudslay, by then in his early 40’s and fully recovered from his ordeal with Malaria, returned to Mexico and sought out the city of Palenque, he too stood back in awe at forest’s enormity, regretting the folly of his mission to uncover its ancient structures. But perhaps also, like the modern observer standing atop a magnificent pyramid with the canopy splayed before him, he saw the dotting peaks from afar and decorated stones at his feet all indicating the presence of a truly magnificent civilization; one well worth exploring.

6) A Note on Photography

Photography in the archaeological sites offers a unique challenge that stems from the rules and limitations set in place in most of the ruins by the Mexican government. In no place is this more obvious then Chichen Itza, where most of the buildings are closed off and can only be photographed from afar. This presents a problem because of the lack of available angles in ones attempt to create a special shot. This becomes especially obvious to those interested in making dynamic wide angle photography of the buildings, and thus one needs to know these limitations and work around them. My first suggestion to combat this is to walk around with two DSLR bodies. One with a regular zoom lens (24-70mm) while the other has a longer zoom lens (70-200mm) ideally with a 1.4x teleconverter to allow for a longer range as well as some wildlife photography. I did use my Tokina 11-16mm DX on a few occasions, but it usually coincided with a bit of luck (the Iguana with El Castillo in the background) or in ruins like Calakmul, an archaeological site with far less restrictions. This sounds obvious but make sure to have a comfortable backpack to carry your gear inside for the long and inevitable hikes involved in fully exploring the ruins. A general rule for all archaeological sites all over the globe is to arrive as early as possible, as it will allow you to somewhat beat the large crowds (Calakmul is an exception since it is relatively off the beaten path) and allows for the best light. The closing times of all the ruins but Calakmul is around an hour or so before sunset, making for sunset photography difficult. Because of this, days with more clouds not only offer more interesting skies, but also help soften the light a bit. I also recommend using polarizing filters, they really help bring out the texture in the rocks and give the sky a punch. Lastly, tripods are not allowed in any of the ruins and this is something that is quite heavily enforced. Plan for using slightly higher ISO because of this.

Here is my recommended kit for the Chichen Itza, Uxmal and Palenque:

- Camera body with 24-70mm Lens (16-50mm on crop) with a Polarizing Filter

- Camera body with 70-200mm Lens + 1.4x TC

- Ultra-Wide Angle Lens

Recommended kit for Calakmul:

- Camera body with 24-70mm Lens (16-50mm on crop) with Polarizing Filter

- Camera body with a fast super telephoto lens (such as 300mm f/2.8)

The post What to Photograph in the Yucatan Peninsula appeared first on Photography Life.