Have you heard of the Orton Effect? This post-processing technique has been around since the 1980s, if not earlier, but the trend has exploded tremendously in the past few years. If you haven’t heard of it, you aren’t alone – it only recently began to gain mainstream popularity. And yet, in some ways, the Orton Effect is swallowing the modern world of landscape photography. This is barely an exaggeration; after seeing the Orton Effect in practice, you should be able to spot it in at least a third of the trending 500px landscape photos, as well as many winning photo contest entries. This article covers all the basics of the Orton Effect, including a tutorial on how to implement it in your own images – and a discussion on why you probably don’t want to do so.

1) What is the Orton Effect?

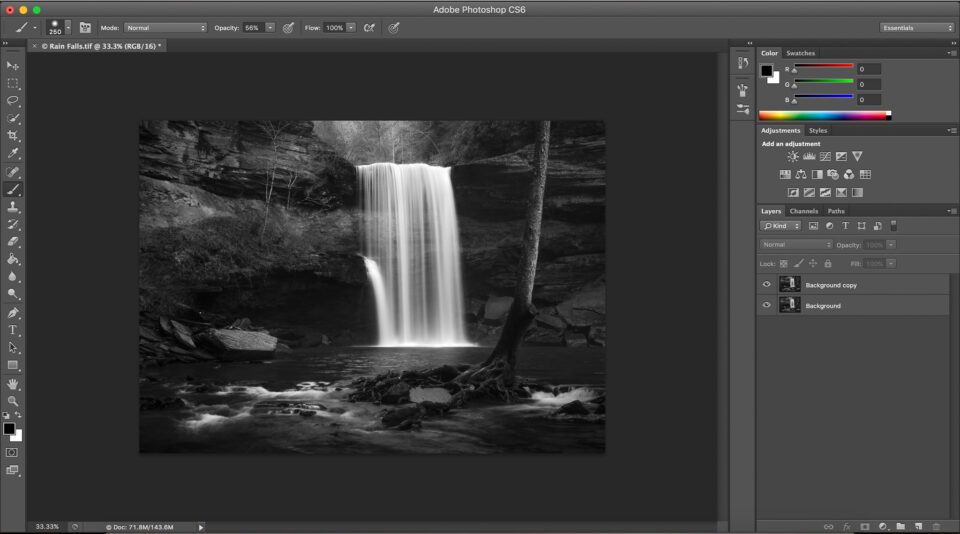

At its most basic, the Orton Effect is a glow added to photographs (typically landscapes) in post-production. In and of itself, that doesn’t seem too harmful. The problem, though, comes when a huge portion of landscape photos have the same glow. Take the photograph below for an exaggerated application of the Orton Effect:

You should be able to tell that something is unusual about the photo above; it has a bizarre glow around it, and certain areas of the photo are hard to focus on. That’s the Orton Effect.

The Orton Effect was created by abstract landscape photographer Michael Orton, and it was originally a technique used in film photography. With film, a photographer would take two images and layer them on top of each other – one that was in focus, and one that was overexposed and out of focus. When layered, the two pieces of film produced a single photograph that was simultaneously sharp and blurry. This technique added a soft glow effect to a photo.

This article is not a reaction against Michael Orton. His photographs are great; you should check out his website if you get the chance. Even his Orton Effect images are so abstract and surreal that they hardly fall under the umbrella of this article.

Instead, I want to focus on the modern-day implementation of the Orton Effect. This technique is overused among digital landscape photographers, and I believe that its proliferation harms our collective idea of creativity.

2) How to Apply the Orton Effect

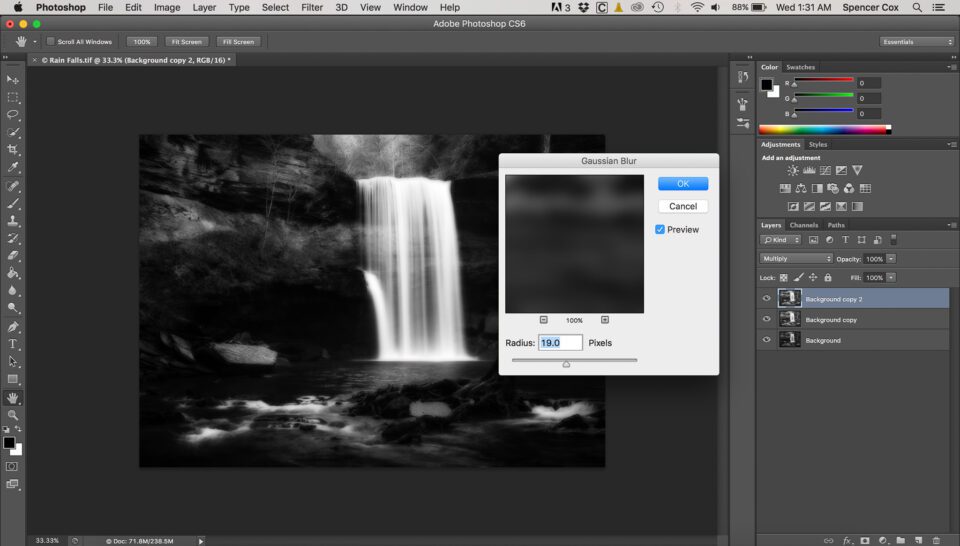

I won’t go into extreme details in this section, since (as I discuss ahead), the last thing I want is an even higher number of photographers defaulting to the Orton Effect. Still, a brief tutorial is below:

- Open your image in Photoshop and duplicate the layer:

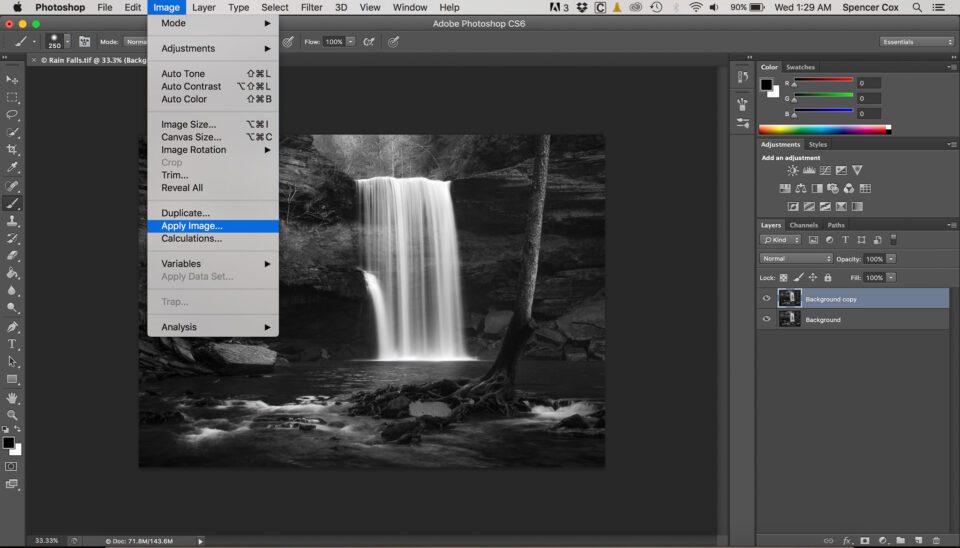

- For the top layer, click Image > Apply Image:

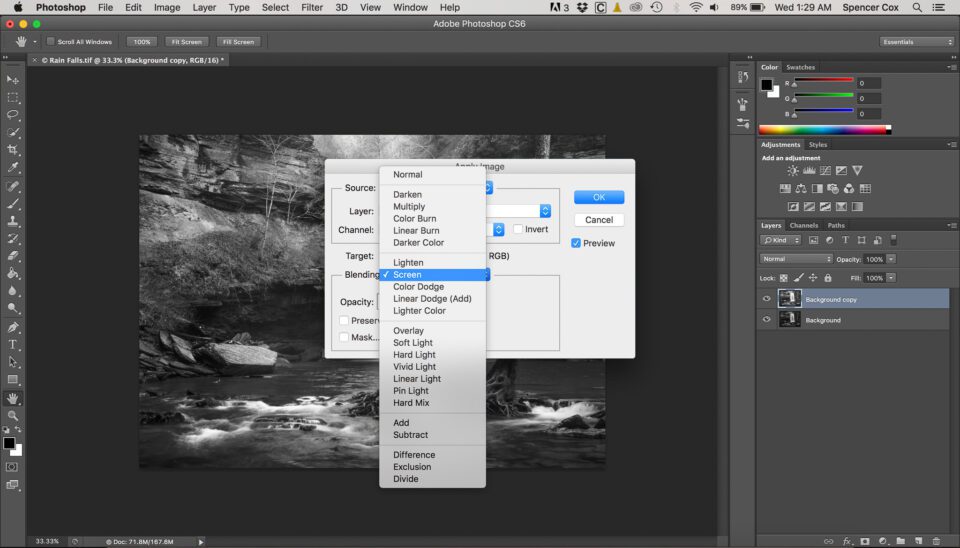

- In the “Apply Image” blending mode, click “Screen” and hit enter:

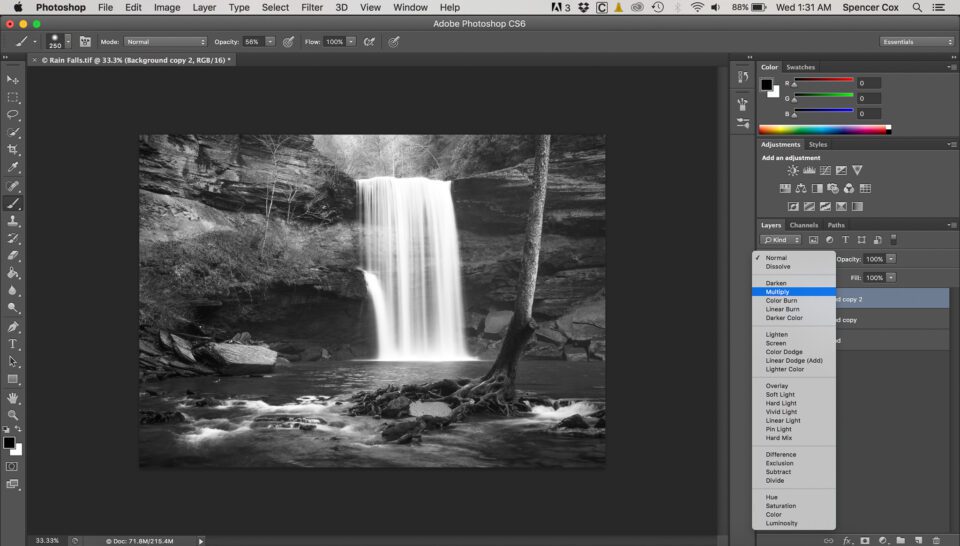

- Duplicate that layer, then click the “Multiply” blending mode:

- Go to Filter > Blur > Gaussian Blur. Adjust to taste:

- Merge the two top layers (Command+e or Control+e) and create a mask to decrease or increase the Orton Effect in different portions of the image. You almost certainly will want to reduce the layer’s opacity, or the effect will be far too strong:

As a final touch, since the Orton Effect darkens the shadows of a photo, you may want to lighten them back in Lightroom or Photoshop.

That’s it; the Orton Effect is pretty simple to implement. However, it does take a few steps in Photoshop, some of which may not be intuitive. Some software has built-in Orton Effect settings, while others (like Lightroom) do not allow for layers and thus cannot be used to create the Orton Effect.

3) Exaggerated Examples of the Orton Effect

In order to show clear examples of the Orton Effect, I have included three before/after comparisons below. These are far more exaggerated than typical implementations of the Orton Effect, but they will help solidify the concept if you are not yet familiar with it.

Here’s an incredibly pronounced example, where I barely reduced the opacity of the Orton Effect layer at all:

This next one is a bit subtler, but pay attention to the trees and rocks near the top of the frame. It’s still pretty pronounced:

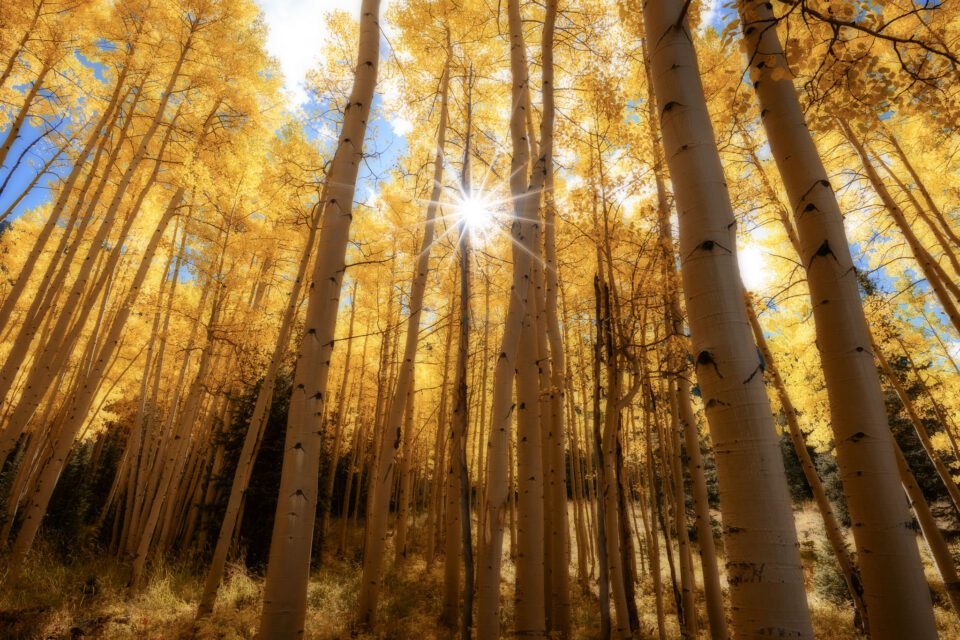

Finally, here’s a landscape that never should have had this soft effect applied in the first place, since it is supposed to be harsh and dramatic:

4) Typical Use of the Orton Effect

The examples above are pronounced, to say the least. Although some photographers do employ the Orton Effect to such extremes, most – including a majority of 500px photos with this effect – are far, far subtler.

Take a look at the landscape photograph below, for example. It has had the Orton Effect applied, but only in certain areas of the frame. This is similar to how many of the photos on 500px appear:

Since you’ve seen some other examples, hopefully you can tell that this photo has the Orton Effect applied. Still, it is much less noticeable than the three comparisons above. (If you’re having a tough time seeing it, pay attention to the glowing spots of grass near the sunbeams; the effect also is more visible on a large monitor.) Photographers who don’t know about this effect – like the vast majority of 500px viewers – may think that the glow in the photo above is simply a natural result of fog. But what if every photo that I took had the exact same “natural” fog? It no longer would add interest to the photo; it would add a creepy sense of uniformity.

5) What’s Wrong with It?

If every photograph of mine employed the Orton Effect, even subtly, they would all start to look the same. Perhaps there is nothing wrong with one or two such photos in someone’s portfolio, but it would be unbearable if every single photo looked exactly like this.

Therein lies the problem. Although not all popular landscape photos employ this technique, a shockingly large portion of them do. While writing this article, I looked at the top fifty trending landscape photos on 500px (which have now changed) for a comparison; I am certain that seventeen of them used this effect, and there were a few others that were too close to tell. Two of them used the Orton Effect so strongly that my eyes began to blur; I started to see a false glow in the real world for a few seconds – not a pleasant experience!

Collectively, photographers don’t yet look at the Orton Effect in the same way that we see over-the-top HDR photography. However, I believe that both – especially when overused – lead to equally garish photographs. Under most circumstances, details in the real world do not have an etherial glow lingering around them; even when employed lightly, the Orton Effect feels “off” from how we experience the world. In subtle doses, the Orton Effect may not be a bad thing. But, in subtle doses across a third of the popular 500px photographs, I think it has run its course.

6) Proceeding from Here

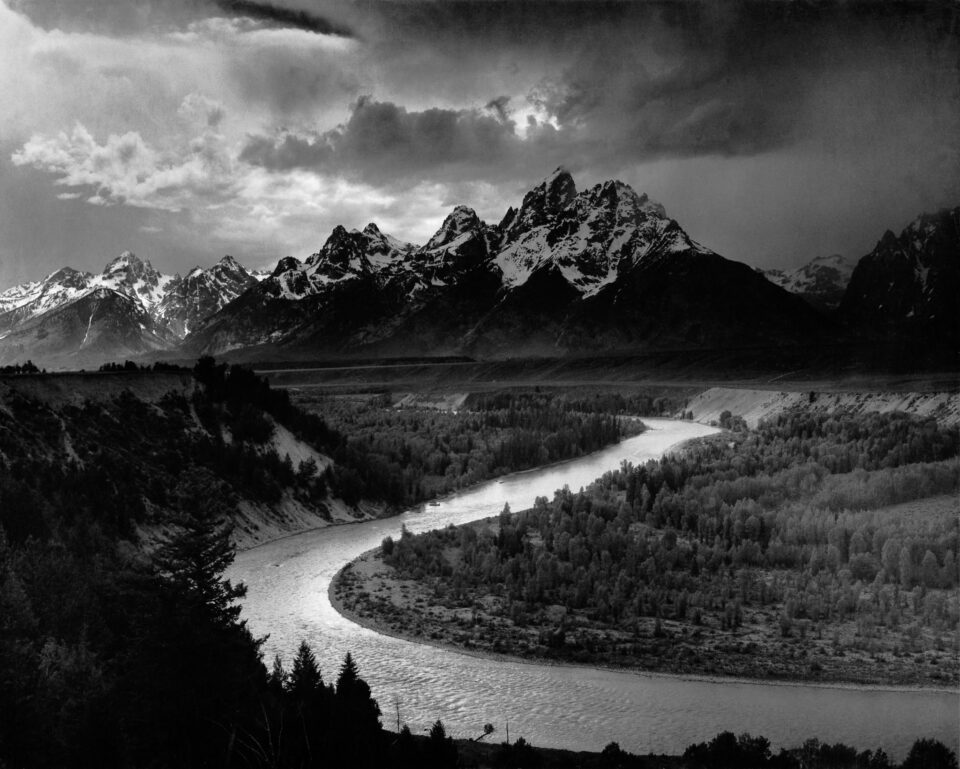

I shared an Ansel Adams photo in a previous article, and it is worth adding here as well:

Feel free to stare at this photograph until your eyes no longer see the world with a cheesy glow effect.

As you can tell, I am not a fan of the Orton Effect’s prevalence today. I believe that it has encroached upon our collective concept of a “good” landscape photograph – its otherworldly glow gives the false appearance of improving every landscape image. In reality, I think it does more harm than good.

Is this post simply a reaction against the mainstream concept of beautiful landscape photography? Am I calling out a system simply because I have different tastes from most people? Perhaps so. I enjoy Ansel Adams’s photos far more than any Orton Effect image; maybe my opinion of photographs is simply stuck in what used to be considered beautiful, and I have yet to move on.

Still, I know what makes a photograph work for me, and it isn’t the Orton Effect. I think that, as photographers, we are far beyond the point of using the Orton Effect reasonably; we have fallen victim to the soft, glowing, faux-beautiful atmosphere of photos that have been adjusted well beyond their inherent value. I am not immune; until recent weeks, I also gravitated to the impossible beauty of these photos. Now, though, I have begun to see the consequences of the Orton Effect. The most popular landscape photos on the world’s largest photography websites are beginning to look like Thomas Kinkade paintings (which you should Google with caution).

7) Conclusion

There is nothing inherently wrong with a post-production glow, even if it looks overdone and fake. But I absolutely believe that there is something wrong when more than a third of the “popular” landscapes on photography boards use the exact same Photoshop effect. We are no longer reacting to the photographs themselves; we are reacting to the presets that have been applied. This isn’t much better than an Instagram filter.

The Orton Effect wouldn’t bother me much, except that it gets almost universal praise from photographers across the internet. Sunrise photos of Mount Fitz Roy with the Orton Effect? They are among the most popular on every photography website. A field of glowing green grass with an extreme Orton Effect? They win photo contests and solicit thousands of Facebook likes. Even if a photo’s quality has nothing to do with its online popularity, all this attention certainly counts for something.

As a final note, if you do use the Orton Effect for your own photographs, please do not take this article as a personal criticism. People certainly love Orton Effect photographs, and it would not surprise me if landscape professionals find that their sales increase with this effect (similar to HDR photographs). In the end, you should feel free to use whatever methods you enjoy; for most photographers, that’s the real point of taking pictures in the first place.

But if you find yourself jealous over the increasing number of overly-beautiful, glowing landscape photos on sites like 500px, don’t feel discouraged. The Orton Effect is rarely more than eye candy, and it loses its “magic” the moment that everyone has access to this technique. A landscape photograph doesn’t need a mystical glow in order to be beautiful; it just needs to represent your personal take on the world.

The post Is The Orton Effect Taking Over Landscape Photography? appeared first on Photography Life.