A momentous cellestial event, one not to be repeated for many years! It was surreal, yesterday, watching astronomical excitement migrate across this country, following the sun and the moon. Congeniality, kindness and an all-embracing sense of awe swept over millions. In these often dark times, where many gatherings are slathered in hate and the lack of hope, the light of sky continues to astound, and lifts our hearts. Just maybe, out in the sea of people staring skyward, there are a few young people for whom the ring of fire in the black sky started a spark in their heart, and a yen to travel beyond and above the earthbound, to the ultimate benefit of humankind.

I was prompted to go out and shoot the below, which millions did, with similar results. I played around a bit, lifting some shadows, hoping for a bit of cloud detail. Made one simple pic, not the best, not the worst. But I had fun, observing from my home town. Nikon Z 9, 800mm f6,3 lens, heavy duty Gitzo tripod. Blessedly simple.

All manner of digital tech makes photographing an eclipse easy, or hard, depending on how much travel, scouting and planning is done. Some folks donned some glasses and pointed an iPhone at the sky. Others hoisted mighty lenses on formidable tripods and tripped the shutter in high speed sequences. Others might have tried multiple exposure possibilities. The results are all over the internet, a fantastic celebration of our universe.

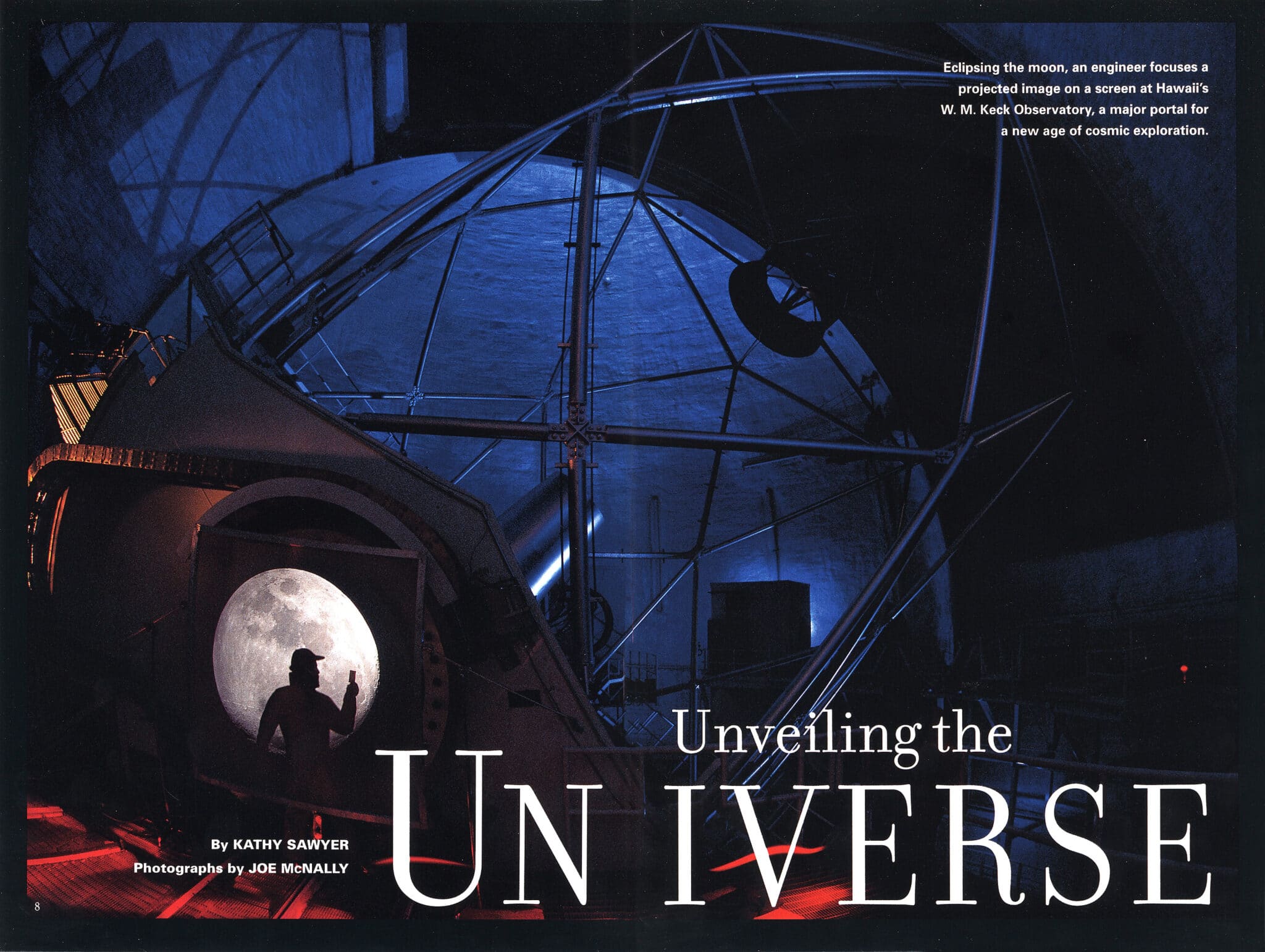

As complex as it can get in the digital world, this whole lunar photo fest brought me back to a story shot long ago, when the National Geographic was still the National Geographic. A story called “The Universe” was turned down by a photographer well established in the Geographic photo sphere. I took it so fast it was hot. Didn’t care that I was not the first photog called. I always looked on these second banana episodes in my career (and there have been many) as an opportunity to show them why I should have been the first call. Being the cussed competitive type that I am, I figured it was my chance to shove the moon up the ass of the office bound top brass at Nat Geo.

My dear friend and frequent collaborator at Nat Geo was Bill Douthitt, who as I have always said, knows more stuff about more stuff than anybody out there. Given the late pulled-plug by the first photog, time had lapsed, and Bill was only able to issue a contract for 12 weeks of work. Which sounds like a lot, but it ain’t, working at this scale of things. He thereafter referred to the story as the “Universe Death March.”

And, lo and behold, a moon picture was in fact was the lead photo. I convinced the very friendly staff of Double Keck in Hawaii to weld a metal frame for me, and I taped it over with vellum. Then they pointed 20 meters worth of mirrors at the very nearby moon. (In planetary terms, the moon is a hop, skip and maybe not even a jump in terms of distance.) This powerful instrument rendered the moon in explosive detail. I positioned a worker in front of the orb, with a focusing device. Presto, lead photo. It took the better part of the day to selectively light the rest of the scope’s cavernous interior. A story for another time.

Photo sleight of hand prevailed on these jobs. The tools available now simply didn’t exist at that point. You kind of had to make choices, and grind it out. For instance, the silhouette of the Very Large Array seen below is available for anyone to shoot with a tripod and a panoramic camera. I could have made that choice. But most likely, this had been done before. My theory on location is to lock it up with something sure fire, then run off the Cliffs of Insanity with a harebrained idea.

If you want something different, something not oft seen, something to stir the collective administrative stupor back at the upper floors of NG headquarters, you had to take on the challenge of lighting a big portion of the whole damn thing.

This ambitious endeavor required two days and a truck load of lighting. It was published, thankfully. Worth it? Yes, for me, on a personal, “stick this in your diddy bag” level. Monetarily? Hmmmm. I worked virtually without sleep on these stories, all day and most of the night. I was paid $ 500 a day. As they say, the challenge is in your bones, and will not be denied or daunted by the numbers.

And, all this photo shenanigans almost landed me a cover. I wanted to show the eternal efforts of the lone individual to look at the night sky. The enthusiast, tilting at the universe with a home based telescope, not one worth hundreds of millions of dollars. So. Had to find an uphill position, with a clean view of the night sky. And a human with a telescope, silhouetted against said night sky.

Now you can’t have someone stand out there all night. At least at editorial rates. We did have a very tall second assistant. I positioned him standing against a piece of 4×8 plywood. Then taped a magic marker to a yardstick, and traced his form. (I had him stand as if he were working the telescope.) Then I jigsawed out his form and spray painted it black. Built a kickstand for it, and went into the field.

I positioned a flash on the backside of the hill, and one pop of the flash backlit him and the scope. And closed the shutter on the three cameras I was working. Which of course meant this whole night’s effort would generate three frames, total. Then put in the cutout. And I re-opened the shutters. Slept in the car that night, and set my watch alarm to three different time slots, thus giving me a three stop bracket on the night sky. These brackets were spread over about six hours. And it was a contender for a cover, which I lost to a picture of a genetically altered pig. Sigh. The such are the slings and arrows of a photographic career.

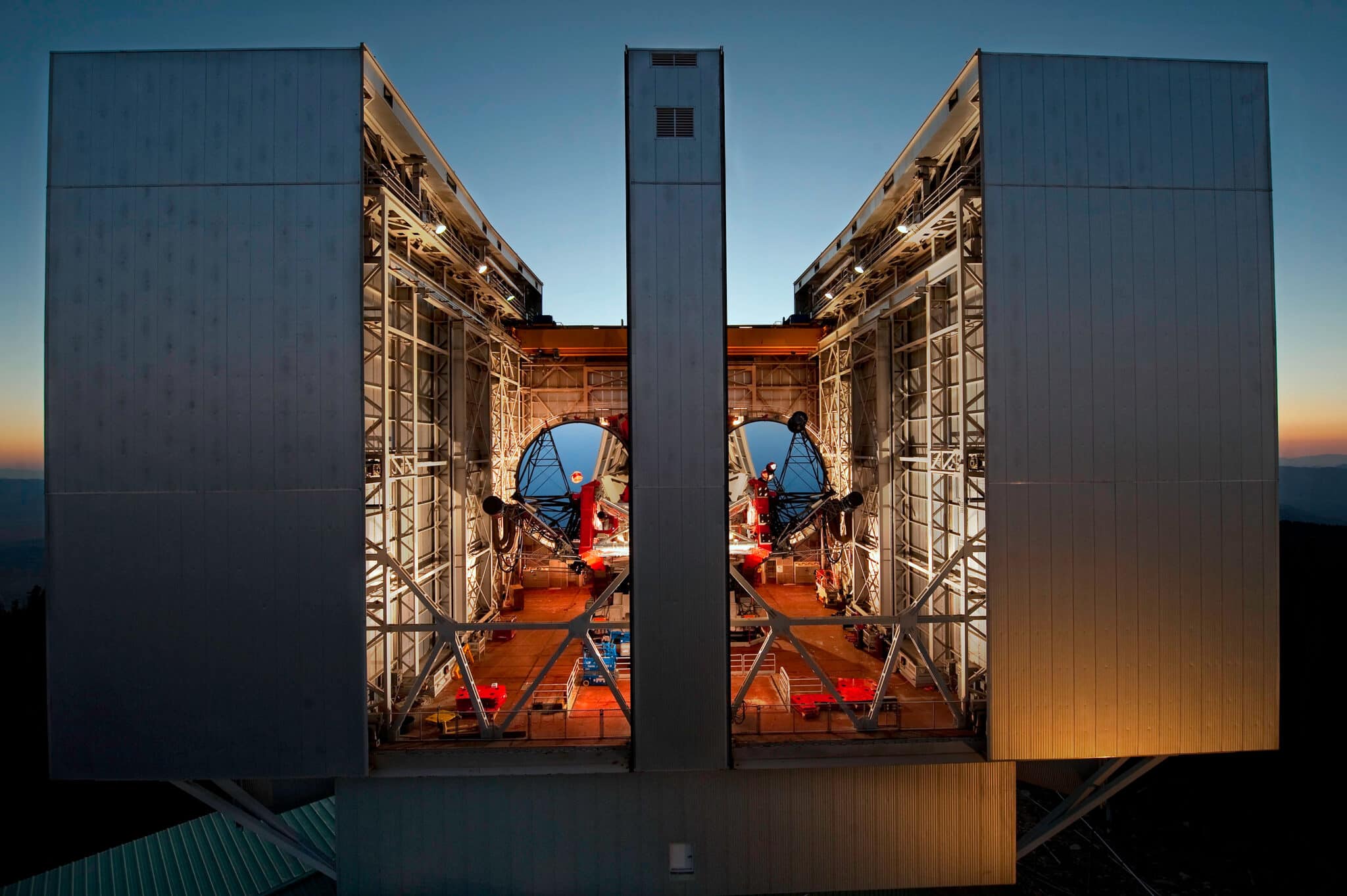

The above was film. But, once you demonstrate a certain capacity for endurance and pursuit of large, inanimate objects located in cold, dark places, Geographic invariably asks you to do it again. This time with digital!

Which did make a pic like the below infinitely easier.

About 20-30,000 watt seconds of light, 175′ boom crane, and about 20 minutes of a sweet spot to make the photo before the mirrors go black, facing the rapidly darkening eastern sky behind me. Digital confirm was very handy here. I had to keep radioing adjustments to the crew from my crane position.The little warm flare of light at the bottom right of the scope is courtesy of the wonderfully talented photog and Brooklyn resident Drew Gurian who worked with me on this story. It’s in some pix, not in others, given the inconsistency of the radio triggers of that time.

Ahh, digital and Nikon Speedlights! The pic below was a walk in the park, by comparison. Six Speedlights, if memory serves.

Did I mention harebrained ideas above? Sigh. An essential part of the story was to somehow note the various methods of imagining space, such as panchromatic, visible with near-infrared, etc. So, I picked the three most graphic renditions I could find of a nebula, I believe, and thought it would be “fun” and informative to the reader to project them on screens in a place known for spectacular night skies and notable, ancient rock formations. Holy shit.

So, exposure-wise, several areas to deal with. Foreground earth, background sky. Totem Pole (rock formation) in distance for scale and depth. Projectors up front. And lighting gear, generators, cooler, Coleman stove, Dinty Moore stew in cans, sleeping bags, and so forth. We pointed three cameras at the scene, in the direction of the famous rocks, but also, important to note, in the general direction of the heavens where the pictured nebula lived, many millions of miles away. Small point, but excellent for the caption.

Also tried this view. It was a long couple of nights out there on the desert floor. There’s tons of flaws in all the efforts here, but NG published the above. Again, no one had really seen this kind of image before. I owe a huge vote of thanks to Dan Bergeron, who is a helluva photog based on the West Coast. His job was to light paint the Totem Pole, which he did with a generator and a number of 2400ws units perched on his pickup truck. I’d open the shutter and give him a radio call to blast away.

The galaxy continues to fascinate us.

More tk.

The post Excitement in the Skies! Solar Eclipse, 2024! appeared first on Joe McNally Photography.